Unlock the Insights That Changed My Life

Each week, I share a glimpse of my ideas and perspectives on life in short 5-minute emails. But there’s so much more depth to explore.

I struggle with memory.

Names.

Dates.

Stuff my wife tells me.

Things I agreed to do but didn’t write down.

It’s frustrating. Embarrassing, even.

But classic me - I needed to figure out the science behind why remembering things even occurs.

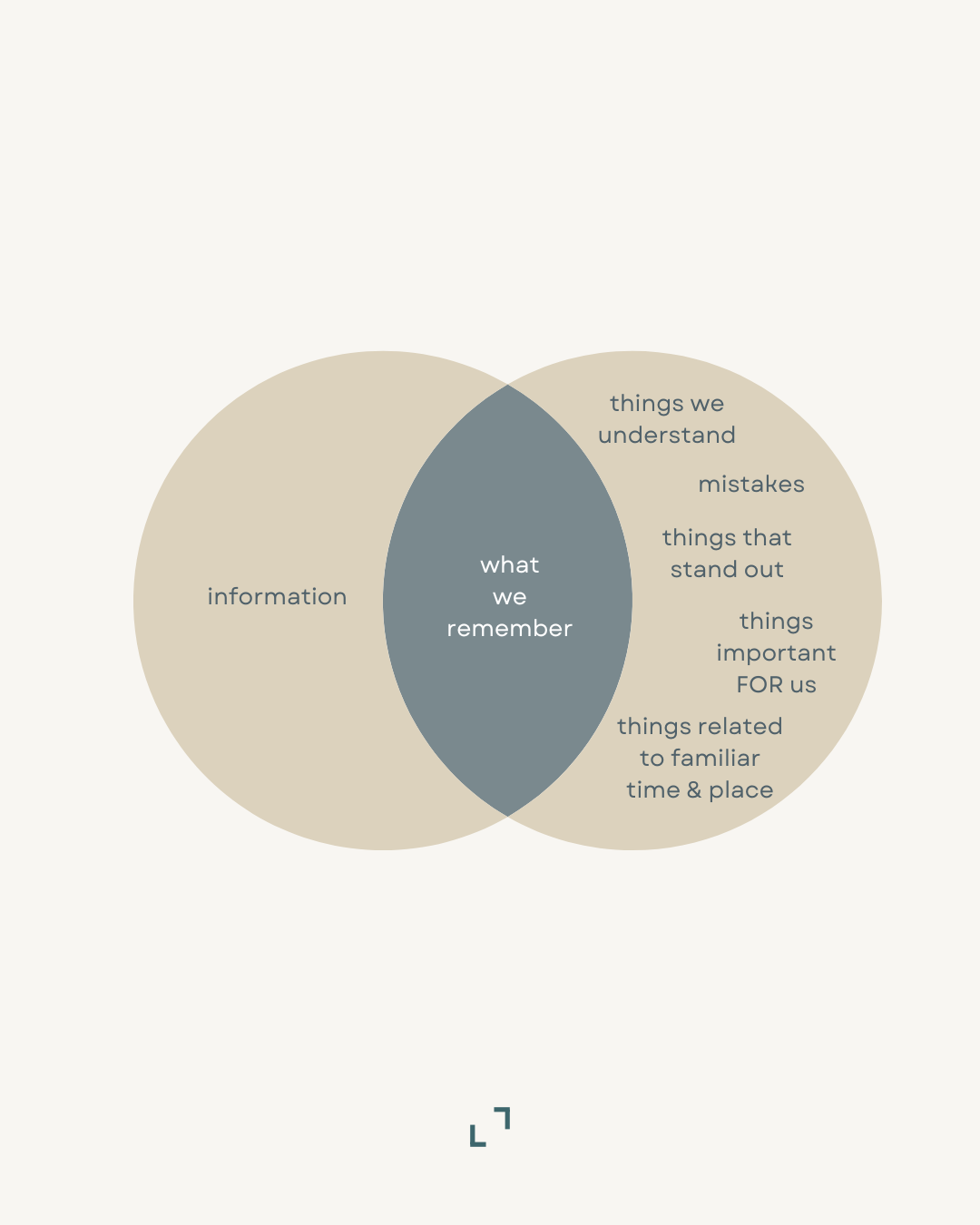

So I did some research, and this is the best explanation I’ve found on what builds the framework for a good memory.

It’s from Dr. Charan Ranganath, cognitive neuroscientist and author of Why We Remember.

He created a simple framework that outlines how memory works.

It’s called MEDIC.

We remember things based on 5 factors:

M - Meaning

You have to understand it.

If you’re a football fan and I talk to you about stats in golf, you won’t remember them the next day.

But if I tell you about the stats of a brand new signing in your favourite Premier League team, you’ll remember them for weeks.

The mind prioritizes what it understands

Meaning gives memory a scaffold.

Without meaning, information becomes noise.

E - Error

Mistakes are sticky - our brain is predisposed to be biased toward negative information.

Therefore, making mistakes while doing something increases the likelihood that you’ll remember it.

That’s why it’s easier to memorise your way around a new city if you drive through it as compared to being driven around in an Uber.

You don’t remember how to do a thing, but all the ways you shouldn’t do it.

You don’t remember a thing - you almost remember all the things that it is not.

D - Distinctive

The mind ignores the ordinary.

But it clings to novelty. To distinction.

Walking down a street, you pass by 100s of people.

Yet remember none of them except the one lady who helped you with your bags from the grocery store.

Or the one homeless person with a parrot on his shoulder.

Distinctiveness = memorability.

Your brain requires details to form neural pathways that light up when prompted for information.

I - Importance

Not what is important to you, but what is important for your survival.

You will remember things that put you in danger, so you can avoid them in the future.

You will remember what made you feel pleasure, so you can repeat them in the future.

The higher the intensity of danger or pleasure, the more vivid the memory.

That’s why trauma exists, and why we remember ecstatic moments so clearly - clearing an exam, getting a promotion, winning a competition…

In emotionally intense states like these—like fear, joy, or stress—the brain releases chemicals like dopamine, noradrenaline, and cortisol.

These substances can enhance brain plasticity and memory consolidation, especially for events linked to survival or strong emotions. However, the effect depends on the intensity and duration of the experience.

(Slight caveat - excess cortisol (stress hormone) can actually impair memory, but in the right dosage can help with memory retention.)

C - Context

Memory isn’t a file you put in a cabinet that you can refer to as and when you want to.

It’s a network. We form memories when they’re tied to contexts.

This boils down to time and place (and sometimes smell).

If you hear a song that you haven’t heard since high school, you’ll suddenly get a rush of memories associated with it that you well… forgot you remembered.

Simply associating the song with a time lets you access them without even trying.

Or why you walk into the kitchen and forget why you came—until you go back to the office, retrace your mental steps, and remember:

Ah. Tea.

Time. Place. Smell. All act as mental bookmarks.

How we can intervene

We tend to think memory is fixed. That we’re either good at it or we’re not.

But memory is malleable. And more importantly, trainable.

Repetition:

Not sexy. But wildly effective.

Repetition is an active intervention on how you can improve your memory about a thing -

Like a book? Read it twice.

Heard a story worth keeping? Tell it to someone else.

Wife telling you something? Repeat it to her to confirm if what you understood is true.

Every repetition strengthens the neural pathway.

It’s like carving a groove deeper each time you pass over it.

But here’s the catch—repetition doesn’t care if something is true.

That’s why fake news spreads.

Repeat a lie often enough, and the brain starts to register it as fact.

Repetition makes beliefs feel familiar.

And familiarity feels like truth.

Perspective

All memory is storytelling.

Nothing you recall is 100% accurate—it’s just your version of events.

(Brain scans record the SAME activity while remembering memories and watching a movie - proving that all our memories are quite literally, stories.)

Consider two people watching the same football game, each supporting the other team.

Both of them will have two different recollections of the details of the game. Not necessarily contradictory, neither of them wrong, but different nonetheless.

The trick then is to shift your perspective -

Change the perspective, and the story changes.

That’s why therapy works. It doesn’t erase the past—it reframes it.

Same memory, new meaning.

Life Hack

If you want to feel better about something, put yourself in another person's shoes -

They don’t even have to be a part of the situation - just try to think the way a third person would (not how you would want them to), and you’ll automatically begin to feel better about it.

🙋🏽♂️Found this newsletter useful?

You can support my work by buying me a coffee. ☕

PS: This is by no means an obligation. You are welcome to scroll past this section and move on to the rest of the newsletter.

But if you want to, and have the means to, feel free to buy me a coffee or two. :)

I will be equally grateful if you share this post with a friend who you think it might help. 👇🏼

Currently Consuming:

Pods

Books

James Clear’s “Atomic Habits”

Mitch Albom’s “Tuesdays with Morrie” (Trying our fiction for this first time in more than a decade)

Drew E Whitman’s “Ca$hvertising”

If you enjoyed reading this newsletter, or think it would be helpful to one of your friends, use one of the buttons below :)

...coincidentally reminds me of Aristotle's 3 unities - Action, Time, Place. Insightful, as most of the plays at the time would be passed down in oral tradition - dramatic storytelling. Could the performing artists have stumbled upon a gnarly neuro-scientific nugget!?